Today, January 20th, is National Cheese Lover’s Day! We’re celebrating by looking back at the cheese lovers who came before us and paved the whey for our obsession today.

The thing is, humankind has been loving cheese pretty much since we learned how to make it. There are a couple of stories about the discovery of cheese – the most well known and apocryphal is the story of a man traveling across the desert with milk in a sheep-stomach bag. After the heat of traveling and the rhythm of the camel he was riding, the milk transformed into whey and curds, which the hungry traveler devoured. While this story is questioned by historians (especially since it was suspected that humans were possibly lactose intolerant before the introduction of cheese into diets), cheesemaking can be traced back at least 4,000 years.

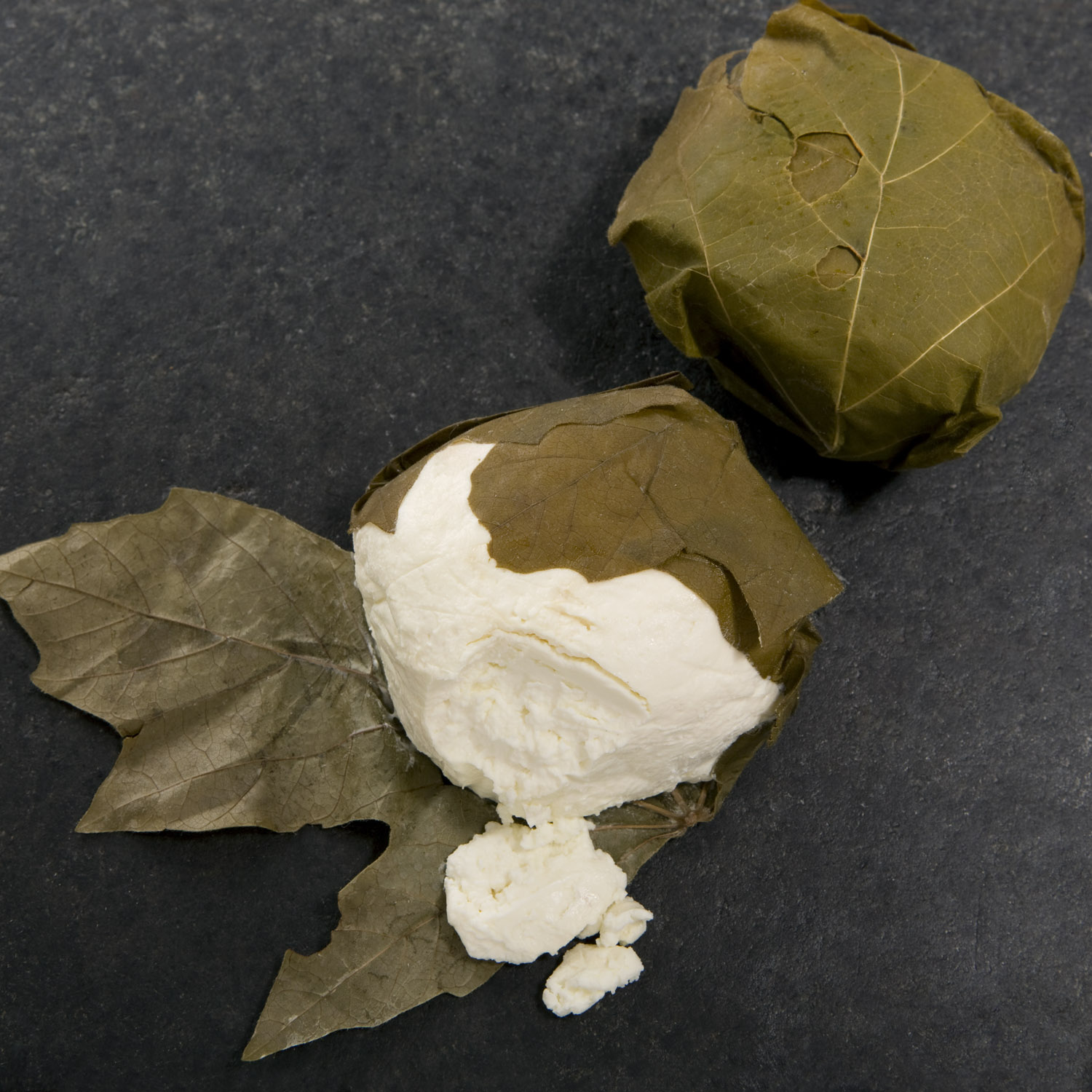

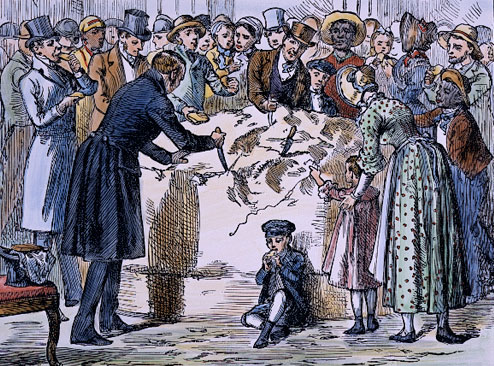

The manufacturing of cheese is depicted in murals in Egyptian tombs that are dated back to 2000 BCE. Jars from the First Dynasty of Egypt were found to contain cheese, dating back to 3000 BCE. Cheeses from this era were thought to be fresh cheeses, and were thought to be made through acid coagulation or through a combination of heat and acid.

(Cheesemaking according to ancient Egyptian heiroglyphics. credit: Oregon State University)

Cheesemaking became a way of life, especially in Europe, during the Middle Ages. Cheese during this period was highly regional, used as a method of bartering and taxing, and was especially important to places such as monasteries. In fact, it was the monasteries of the French and Swiss regions that developed one of the most beloved style of cheeses – the washed rind. Whether it was accidental (there is an excellent story of a drunken monk spilling his beer over an aging wheel of cheese that resulted in it’s funky exterior) or an experimental process, we came up with delicious, pungent wheels that are still enjoyed to this day. Also during the Medieval period, cheese such as Gorgonzola in the Po River Valley (897 CE), Roquefort by French monks (1070 CE), and English Cheddar (1500 CE) were developed, with their traditions continuing on to this day.

While we’ve talked plenty about cheesemaking in the Middle East and Europe, we haven’t talked much about the Americas. This mostly has to do with fact that cheesemaking simply was non-existent prior to European immigration to the Americas. Columbus brought goats on his voyages as a source of constant milk and cheese for the long voyage. The Mayflower included cheese among their supplies while crossing the Atlantic in 1620, and brought cheesemaking to the colonies as they raised livestock.

As American cheese production developed during the 18th and 19th centuries, it became clear that cheese was as regional as it was in Europe. English and Irish immigrants brought cheddar to New England, while the Swiss and Germans developed the Alpine recipes of their homeland in the Midwest (especially Wisconsin). Out on the West Coast, Spanish and Italian missionaries who had moved up and over the Mexican border brought their own style of aged goat and sheep’s milk cheeses.

It wasn’t just local farmers who were getting in on the action – inspired by his travels in Paris and Northern Italy, President Thomas Jefferson fell in love with a recipe there. For a state dinner, the President imported macaroni and Parmesan cheese. Dubbed “a pie called macaroni”, Thomas Jefferson unwittingly introduced macaroni and cheese to the American consciousness.

(above, Thomas Jefferson’s initial sketches of a pasta machine, which he would use to make the United States’ first version of macaroni and cheese. credit: Library of Congress)

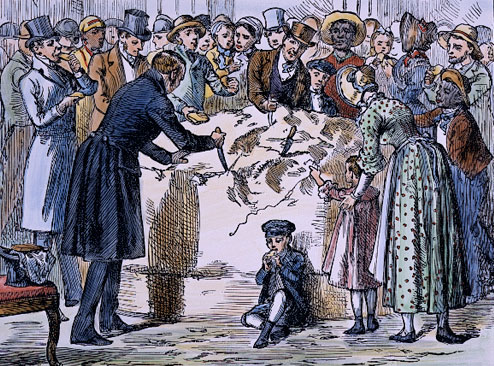

But Thomas Jefferson wasn’t the only American president who enjoyed cheese. In 1835, Colonel Thomas Meacham, who was a dairy farmer from Sandy Creek, NY, made a gigantic wheel of cheddar. Four feet wide, and two feet thick, it weighted nearly 1400 lbs, and was dedicated to the current President of the United States, Andrew Jackson. But Meacham didn’t just dedicate that big block of cheese – he sent it to Jackson. When it arrived at the White House, Jackson was left wondering what exactly to do with it. It certainly didn’t help that the cheese was described, by one senator, as “an evil-smelling horror” that supposedly could be smelled from blocks away.

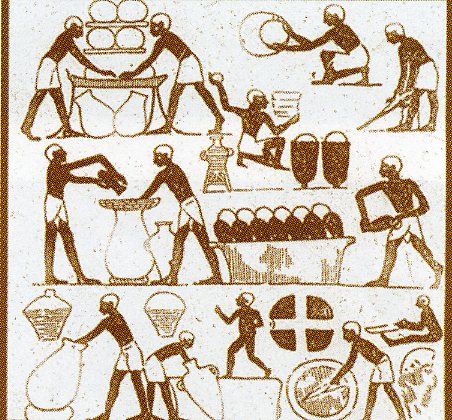

Jackson tried to get rid of it by handing out large chunks to friends and family, but two years later, there was still about 1200 lbs of cheese remaining. With his term almost up, Jackson sure wasn’t going to be bringing what remained of the cheese with him when he left the Oval Office. During his last public reception at the White House, Jackson opened the doors of the White House to his constituents, who swarmed the atrium. 10,000 people attacked the wheel, hacking into it with knives and walking away with sizable chunks. Jackson’s plan worked – after two hours, the entire wheel was gone, and Jackson was rid of his stinky cheddar.

(above, an illustration of Jackson’s big block of cheese, as the public attacks it with vigor. credit: Mental Floss)

Things in American cheesemaking began to change in the mid-nineteenth century, with the construction of the United States’ first cheese factory. Built in 1851 in Oneida County, New York, by a Mr. Jesse Williams. The father half of a father-son venture, Jesse’s boy wasn’t exactly the most skilled cheesemaker that had been born to the family. By buying milk from surrounding herds and pooling it to make a factory-made cheese, he covered up his son’s lack of skill, while making a bulk cheese that was affordable and less labor intensive. And like that, cheesemakers started changing to the factory style, which made them a much prettier penny than their small-scale farmhouse businesses had in the past.

The small time farmer’s cheese production slowly dwindled over the early 1900’s, but it was World War II that wiped out the regional diversity of US cheese. (The same thing, we should note, happened in Europe as well, and the war almost killed off some of our most beloved imported recipes.) Due to rationing, streamlining commodity cheeses in factories was an important wartime effort and a way of saving money while providing cheese for the nation. The cheese business was consolidated, for the sake of winning the war.

That was the state of American cheese for a good 30 years after the war – a desolate wasteland of “cheese food” and “cheese product”. Sure, we discovered that the mild, meltable processed American cheese was perfect for topping a burger or melting in a grilled cheese. But we, as a nation, missed the flavor of the Old World traditions that had been lost.

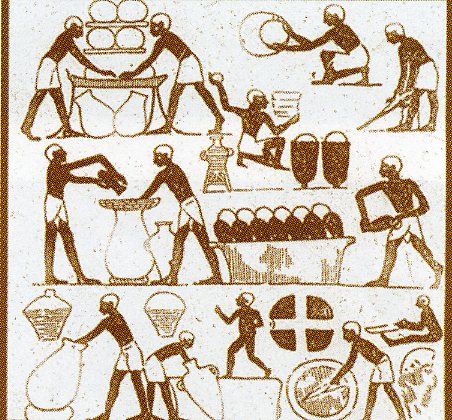

But the 1970’s birthed the artisan cheese revival! Started by women and small town farmers trying to re-establish their connection with Old World traditions, the focus began using goat and sheep’s milk instead of cow’s milk. While the yield of these cheeses was low and a more expensive product, the quality could not be denied. Cheesemakers like Laura Chenel, Vermont Creamery, and Cypress Grove had little to start with, but trained in French techniques and brought flavor back to the American cheese industry, from the ground up. Since then, the American cheesemaking scene has blown up, the artisan cheese boom giving birth to some of our favorite cheeses Bayley Hazen Blue, Pleasant Ridge Reserve, and Coupole.