Aaron Foster is Head Buyer at Murray’s Cheese. His relentless pursuit of all things delicious most recently led him to the mountains of France, where he discovered the best wheel of Comté we’ve ever tasted.

Tap Tap Tap Tap Tap.

Tap Tap Tap.

Tap Tap Tap Tap.

The cellar master at Marcel Petite smacks the hammer-end of his cheese iron against an 80 lb wheel of Comté. He hushes us with his eyes and pricks up his ears to listen for any changes in the uniform tapping sound. A slight drop in pitch or a hollow-sounding tap instead of a flat one might indicate a problem with quality, like eyeing or cracking in the interior cheese. He finds a dull spot, and draws our attention as he taps it again. Straining to listen carefully, I can almost imagine hearing a difference between that spot and all the others. Truth be told – I hear no difference at all.

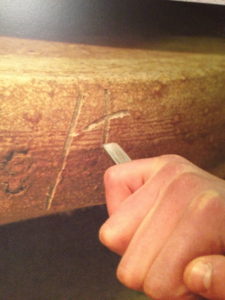

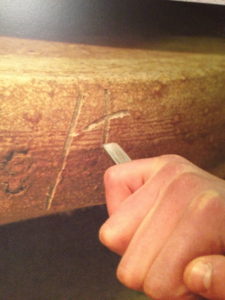

As if to prove his mettle, he turns the cheese iron around and uses the sharp end to pierce the spot where he suspects the defect to be. Out comes a core sample of the cheese, and sure enough, a small eye dots the center of the piece. He passes around a bean-sized taste to each of us, which we savor, paying no mind to the minuscule “defect”. He pops the remainder of the core back into the cheese and smooths over the rind. If you didn’t know, you could hardly tell we were there. He uses the iron to etch a small symbol into the outside of the wheel – an indication, he says, of the defect and of how long he expects that particular wheel to mature. A lot of information for what looks like a 3-inch backslash on a round of cheese as big as a wagon wheel. But it’s more than enough for the team at Marcel Petite. These folks know their cheese.

Standing in a 19th Century fort surrounded by tens of thousands of wheels of cheese, it’s a strange sensation. Of course, 150 years ago you’d be wandering in between soldiers’ quarters and munitions depots. Fort St. Antoine (originally Fort Lucotte) was built to defend against the threat of an aggressive Prussian force, not to warehouse untold tons of fromage. Ironically, the Franco-Prussian war ended almost simultaneously with the completion of the fort, and for the next century, it sat essentially empty.

The subterranean construction and quarried stone edifices mean the fort holds a relatively constant temperature and humidity, around 46 degrees Fahrenheit and 95% humidity. The cool, damp, and dark setting no doubt made for some uncomfortable sleeping arrangements for the French soldiers stationed there, but it’s perfect for maturing Comté.

We’re in a large vault in the caves, almost 40 feet high, with Comté stacked floor to ceiling. I find myself wondering how the wheels all the way up at the top get washed, brushed, flipped, and tasted. As if on cue, I hear a gentle whirring sound in the next aisle over. Craning my head around the corner, I come face to face with a large… robot, for lack of a better word. More benign than HAL 9000 and less adorable than Johnny 5, Marcel Petite employs these robots to troll the stacks of Comté 24/7/365. They perform the Sisyphean tasks associated with maturing the 100,000 wheels of cheese that inhabit the fort at any one time.

Even more remarkable than the robotic feats of affinage are the human ones. The cellar masters of Marcel Petite taste every single wheel that enters the fort at least once, and up to four times before it’s sold! Every wheel of every batch gets the same tap tap tap to identify defects, every wheel is cored and tasted thoughtfully, and then marked with symbols to help guide the affineurs. This isn’t the most astounding part of the process.

What truly boggles the mind is the fact that all of this information, the tasting notes, the symbols, the tapping… it isn’t computerized or recorded in some master database. It’s a completely analog system. The tasters simply remember what each batch tastes like. Sure they write some crib notes on the side of the wheel. But their taste memory is so sophisticated, that they can remember the specific flavor nuances of hundreds if not thousands of batches of cheese at a time. It’s superhuman. And they can even extrapolate what a cheese of 4 months might taste like at 14 months old, and remember that a year down the line.

It’s this unique skill that allows the team at Marcel Petite to zero in on a flavor profile for Murray’s Cheese. We arrived at the fort with a goal: to find a Comté that matched our ideal of the cheese – the platonic form of Comté. We wanted something as close to perfection as possible. But perfection is rare, like a needle in a haystack, or one wheel of cheese in a thousand.

Comté can exhibit a whole range of flavors – from hazelnut to apricot to cultured butter to nutmeg to egg yolk to leek to bread crust, and everywhere in between. A great table Comté is above all balanced, with a strong yet not aggressive taste, and tension between the fruity, nutty, and savory aspects.

For the first hour or two, it was less about finding our cheese and more about establishing a shared “vocabulary”. Were we tasting the same flavors that the cellar team was detecting? Did we call them by the same names? In this context, tasting is a subjective identification of flavor compounds and molecules that are objectively there. We needed to make sure that what they called “stone fruit” we didn’t identify as “citrus”; that their “nutty” wasn’t our “bready”.

Once we established a baseline and they understood what it was we were searching for, and how we put it in words, the real fun began. Our hosts José and Philipe darted from aisle to aisle, and pulled down wheel after wheel of cheese, each one closer to the mark than the last. Their ritual for tasting created a bizarre sort of anticipation. They would remove a cheese from the stack, read the inscrutable code on the side, test it for defects, and then core it. They’d then step off to the side, sniff the cheese core, and then taste it. Whispers and looks are exchanged, some hushed fragments of conversation. After what seemed like forever, they’d look to us, and usually smile, handing a small bit to each of us to savor.

José’s impressive flavor memory did not fail us. Before long, we’d zeroed in on just two fruitières, and the wheels made during Spring and Fall. Something about the cheese made during the transition from Winter to Summer and vice versa spoke to us. These cheeses had exactly that tension we loved. The earthy tones of well-toasted bread and ripe plums anchored the treble notes of yogurt, grass, even cardamom. We had been seeking balance, and here we found it. Success!

Satisfied with a job well done, we ambled toward the office to share a glass of local wine with our hosts before heading back down the mountain. On the way we passed a dark alcove, and he motioned for us to enter. This small room housed the crème de la crème – the reserve Cru des Sapins that matures for upwards of 24 months, or even longer. Far less than 1% of the cheese matured at the fort has the capacity to age this long and retain the finesse and refinement that Marcel Petite insists on.

Philipe zeroed in on four wheels of reserve Comté that he’s been keeping an eye on for nearly two years. He generously sampled one for us… and we were bowled over. All the flavors we’d been seeking were there, but distilled and intensified. Yet it still retained a balance and elegance that made it seem almost like a tight-rope act for the palate. The longing on our faces must have been apparent. Before we could even speak the words, he had agreed to send us the last wheels of the batch, to celebrate Murray’s new partnership with Marcel Petite.

We’re honored and proud to share this cheese with you. It’s a one time shot, and when it’s gone, it’s gone. Rest assured, our Murray’s Cave Aged Comté will always be extraordinarily special, and always in stock.