by Connor Pelcher

The first British settlers arrived in Jamestown in 1607, bringing hope – and hogs. The pigs were left to their own devices, rapturously descending on the wild nuts and acorns scattered throughout the lush Virginia woodland.

By spring, the Jamestown colonists were keeping their hogs on an island just across the river from the Jamestown settlement. The pigs loved roaming through the thickets and streams, and the farmers could rest easy knowing they wouldn’t wander away. The island soon became known as Hog Island, and still is today, over three centuries later.

But well before English colonists came ashore, and before their hogs rooted through the swamps and sea-meadows of Virginia, Native Americans inhabited the area, smoking, salting, and drying wild fish and game, taking full advantage of that which the forests and ocean bountifully provided.

With the help of the natives, these early colonists adapted their meat preservation techniques to fit their own needs. They began rubbing the pork with salt obtained from evaporating seawater, forcing out the moisture from inside the meat, prohibiting the growth of harmful bacteria. They finished the hams by smoking them over hickory and oak fires and leaving them to age for up to a year. These cured hams proved to be a reliable source of income for the colonists during a time when the prices of cotton or tobacco could fluctuate wildly from season to season.

In 1926, S. Wallace Edwards, the young and affable captain of the Jamestown-Surry ferry, began selling ham sandwiches to his passengers. The ham had been cured by him, according to their generations-old family recipe, on the farm that carried his family name. Before long, the demand for his hams let him quit the ferry business and cure meat full time, eventually growing his business to a nationwide operation.

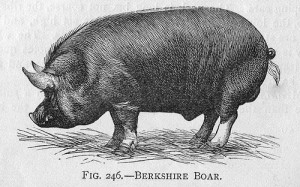

Surryano ham is still made according to the time-honored family recipe: cold-smoked for seven full days and aged for another 18 months. The Edwards family treats their heirloom six-spotted Berkshire hogs with the love and attention that their forbears would lavish upon their own livestock; after roaming the pasture all day, they get a rich, fatty dessert of raw Virginia peanuts.

Surryano ham is still made according to the time-honored family recipe: cold-smoked for seven full days and aged for another 18 months. The Edwards family treats their heirloom six-spotted Berkshire hogs with the love and attention that their forbears would lavish upon their own livestock; after roaming the pasture all day, they get a rich, fatty dessert of raw Virginia peanuts.

That diet and exercise lends a deep, mahogany color and nutty flavor to the amply marbled meat. The smoke adds a stunningly complex depth to the palate, complimenting the flavor of the pork without overpowering it. The plentiful streaks of taupe fat melt on your tongue and coat your mouth with flavor.

While Surryano can be melted on a flatbread pizza, rendered for a savory pasta dish, or even wrapped around melon, the true appreciation for this meat can only be achieved by eating it straight – one perfect, smoky slice at a time.

Connor’s Homemade Surryano Ravioli

Surryano Ravioli

Cloumage, Parmesan, Thyme, Brown Butter

Serves 6

3 cups all-purpose flour

1 tsp salt

4 eggs plus 1 yolk, for wash

2 tsp olive oil

1 sprig fresh thyme

1 tsp minced garlic

¼ lb butter

¼ cup grated Parmigiano-Reggiano

1 10oz container Shy Brothers Cloumage

1 4oz package sliced Surry Farms Surryano Ham

Combine 2 ½ cups flour and salt in a stand mixer. Mix on low with a dough hook and add the eggs one at a time. Slowly add the oil. Finish by adding the rest of the flour until the dough forms a ball. Wrap the dough in plastic wrap and rest for 30 minutes.

With a sharp chef’s knife, cut the Surryano into small squares. Mix with Parmigiano-Reggiano and Cloumage in a mixing bowl.

Remove the dough ball from the plastic wrap and cut it in half. Dust a large portion of your counter with flour and form each half into a rectangle. Feed it through the pasta machine two or three times before reducing the setting. Continue until the machine is at its narrowest setting. The dough should be paper- thin.

Lay out the dough on the floured counter. Brush half of the sheet with the extra egg yolk. Spoon a tablespoon of the Cloumage filling onto the pasta, about two inches apart in a grid. Fold the other half of the pasta sheet over and use your fingers to push out excess air around each mound to form a seal. Use a knife or a crimper to cut out each ravioli.

Melt the butter in a sauté pan over medium heat until the milk solids separate and begin to turn brown. Add the garlic and thyme and lower the heat. Cook for about a minute and remove the sprig of thyme.

Cook the ravioli in salted, boiling water for 4-6 minutes. Serve with the brown butter sauce.